Scouting Reports vs Funding Decks

This week, a basketball player recently rated the “most overrated” by NBA peers led his 4th-seeded team into the NBA finals and took an improbable game 1 victory from the jaws of defeat.

I’ve watched less live sports as I’ve grown older, but I still get hooked by these stories of great athletes who rise to the occasion when people bet against them. Youtube has recognized this and suggests I watch videos like this:

Spoiler alert: Stephen Curry has been a far more valuable NBA player than the six men drafted ahead of him in 2009. Some other big-name athletes that were undervalued coming into professional ranks include:

Tom Brady, largely regarded as the best quarterback of all time, was selected 199th overall (6th round) in the 2000 NFL draft.

Baseball legend Mike Piazza reached Cooperstown (baseball’s Hall of Fame) despite being chosen 1,390th overall 👀 in the 1988 draft.

Other heroes have even gone undrafted then become world champions.

It’s not for teams’ lack of effort to scout players that these athletes and many others are overlooked coming into professional ranks. It’s estimated that the top five professional sports leagues by budget (MLB, NFL, NBA, NHL, and English Premier League) employ a total of approximately 4,000 humans dedicated exclusively to scouting player talent. That’s a roughly even number as players enrolled on those teams’ top-level rosters.

Pinning down the future value of athletes is difficult. There’s plenty of “science” you can apply in the form of analytics and prediction models, and it would be perilous to ignore those analytics. But the best analytics still lead to imprecise projections of a player’s long-term value. The younger they are, the wider the degree of error. Imagine if NBA teams could only draft players under the age of 16: most players would take several years to mature before it becomes evident whether they will ever become a professional talent, let alone a valuable pick.

Projecting player value is a skill, but so is a player outperforming expectations.

Just as scouts miss hidden gems on the field, investment analysts often overlook first-time founders.

Business scouting is big business, but…

Companies and business deals also have scouts; they have titles like “investment analyst”. Like scouting in professional sports, analysts seek to maximize the value of their picks and deal negotiations. Except, business analysis is a game that’s orders of magnitude greater than sports analysis.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are more than 400,000 people in the US with some sort of “financial analyst” role. That includes internal roles within companies, but also entire industries of external-facing analysts in financial advisory, venture capital, private equity, real estate, and investment banking. Helping capital holders find the best value investments is big business.

For all that, many founders with an idea will find it hard to be entice investors. Entrepreneurs regularly expend massive effort to be noticed by investors, whether their plan represents a game-changing startup, a small business, or a plot of land that could be a valuable building for a community. Most “scouting” effort is focused on large businesses and experienced, well-connected operators. Entrepreneurs, especially first-timers, often feel like as though they are hustling for an invitation to try-outs rather than sitting comfortably in a draft lobby.

Your story becomes your scouting report

If you find yourself in an “underdog” position in the business world, feeling unlikely to get find support from investors but dreaming of breaking in, it’s important to understand a few key principles:

1. Emotion over data

Investors are human, and humans are emotional. Figures don’t live rent-free in the brain; narratives do.

2. Stories are shared

Your narrative rarely starts and ends with a single person or group. If it does, it’s dead. Even if your audience doesn’t proactively map out where to share your story right away, they may recall it later in a relevant situation, and that’s when they’ll share their impression.

3. Design for shareability

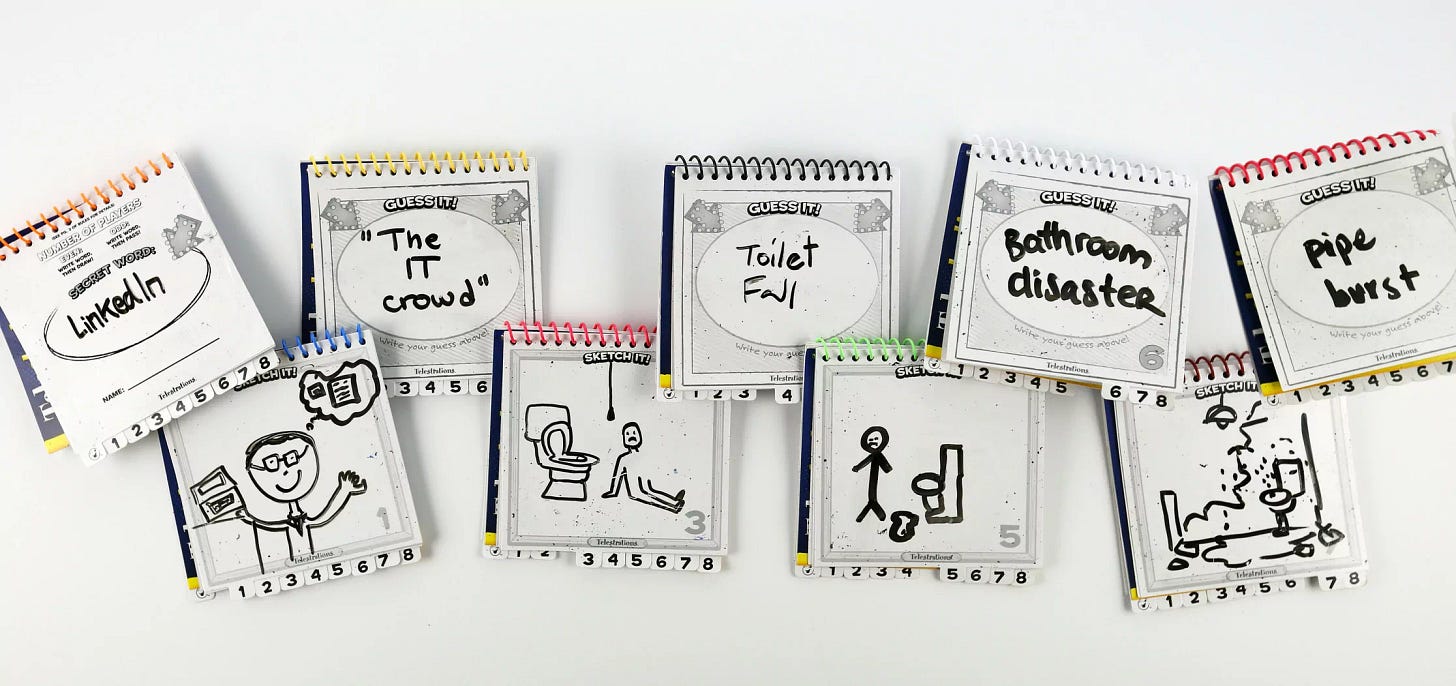

Have you ever played the party game “Telestrations”? It goes by a few names, but this is the gist:

Player one writes down a word, flips the page, and draws a picture of the word.

Player two receives the picture, flips the page, and guesses the word.

Player three reads the guess, flips the page, and draws it.

Repeat until everyone has guessed or drawn.

It’s the game “telephone” where every other hop is a picture. The original word is lost quickly unless the players are strong illustrators.

While Telestrations is a blast because it’s hilarious to see ideas devolve as they spread, it’s far less humorous to a founder when their ideas devolve as they spread through their network. Idea entropy is a real problem.

This is where a pitch deck gets its real job.

Honing your deck to protect the narrative

It’s incumbent on the business leader to produce a self-scouting report on their business deal that will accurately represent the opportunity while the game of telephone proliferates. To do that, the pitch deck needs to be precise and compelling.

The deck’s double duty

A pitch deck needs to be compelling for two separate reasons, really:

Convince investors on the merits of the deal.

Ensure shareworthiness

A classic first-time founder mistake regarding business plans and pitch decks is to ask for a non-disclosure agreement (“NDA”) before sharing anything. There are times when this makes sense, but it’s the exception, not the rule. In most cases, you want people sharing your deck, otherwise they’ll share only an incomplete “telestration” of it, anyway.

An unfortunate side effect of creating a compelling deck and letting it spread is that sometimes a competitor will receive it. Unless the deck contains some extremely proprietary scientific information, the right move is likely just to accept the risk of competitors receiving your plan and move on. Most business is won through momentum and execution, rather than hiding your ideas most effectively.

Necessary and sufficient

A compelling founder story and a great design are necessary but not sufficient components of a successful capital raising deck. Reaching a sufficient amount of information is slightly different depending on the industry, and it actually comes down to the audience (type of investor) to determine exactly what they want to see. But here it is in broad strokes:

Once again this is broad strokes, and different investors may want to see different details. But across these major disciplines, the themes remain the same.

Playing the underdog

For all the preparation and conditioning to get ready for investors, including the spiffing up of your capital deck as much as possible to support your outreach, the reality is that raising capital often brings challenges. It brings rejection. Often you’ll feel like an underdog.

When you feel that way, maybe watch some sports. Maybe like me it will be the first time in a while, but you’ll find an athlete who has been preparing for a big moment for their entire lives, now facing odds stacked against them, and just maybe, you’ll see that underdog rise to the occasion.

As a founder, you won’t always have the same resources as your competitors. Instead of envy, work the process, keep preparing, and when it’s game time, don’t give up.